Published on September 12, 2013

For the silk textile lover, the ASEAN region contains a treasure trove of the most stunning handwoven fabrics found anywhere in the world. These textiles are astounding in their diversity: from the ikats of Cambodia and Thailand, to the golden songket of Indonesia and Malaysia, to the Philippine pina silk and the Burmese acheik — each country offers its own centuries-old weaving traditions that are delectably unique and must-explores for visitors. Factory production and technology have undoubtedly taken a toll on this piece of Southeast Asian culture, one that demands skill, precision and patience, but a visit to virtually any ASEAN country reveals the stubborn and glorious survival of these exquisite textiles. Courtney Norris takes us on a quick tour of Southeast Asian silks.

Brunei Darussalam

Handweaving in Brunei, as in many other parts of Southeast Asia, has undergone a revitalization in recent years, in recognition of its deep cultural importance. Brunei is most famous for its sumptuous jong sarat, a brocade of silk and/or cotton painstakingly interwoven with precious gold and silver thread. In traditional wedding ceremonies, the bride and groom exchange the jong sarat as a symbol of their love and future harmony.

Other special woven fabrics are essential in ceremonial occasions such as the birth of the first child, a boy’s coming-of-age and death in the family. Handwoven silk also plays an important role in royal and state occasions. Diginitaries wear their traditional Malay costumes complete with kain samping, a type of sarong, and arat, or belt made of woven cloth. The color and the design of the silk reveal the status of the wearer.

Kampong Ayer, one of the world’s largest stilted water villages located outside of the capital city of Bandar Seri Begawan, is a hub for spinning and weaving. In addition to the jong sarat, more complex designs can be found here—the silubang bangsi (“hole of flute”) has a complicated floral motif woven throughout and a large punca, or back

design; a typical sarong length takes a month to complete. Most of the woven motifs found in Brunei are inspired by local plants and flowers that are transformed into geometrical forms. The Brunei Arts and Handicraft Training Centre in Kota Batu offers weaving courses and has trained a generation of local weavers in the silk weaving craft.

Cambodia

Cambodia’s rich weaving tradition suffered tremendously during the war years — the magnitude of loss of skilled artisans and knowledge was staggering. Silk weaving and sericulture is slowly being rebuilt, in part due to the efforts of non-governmental and aid organizations who view it as a way of reducing poverty and improving livelihoods, especially among women.

Weaving at the household and village level is done on large wooden frame looms, often under stilt houses. Intricate Cambodian ikats (hol) are world-renowned. Ikat (derived from the Malay word mengikat, meaning to tie or to bind) is the method of creating patterns by dying hanks of thread tied with fiber resists. It can take up to several days or more to produce one meter of an intricate ikat pattern. Ikat patterns were traditionally passed from generation to generation by memory; prior to the war, more than 200 different patterns were known to be in existence, but it is unclear how many have survived.

Artisans Angkor, located in both Siem Reap and Phnom Penh, trains young Cambodians from rural areas in the art of weaving and other Cambodian crafts. Their silkworm farm in Siem Reap, open to the public, provides training in sericulture for a new generation.

Khmer Silk Villages (KSV) also provides technical support to sericulture farmers and weaving communities throughout Cambodia. KSV has a showroom in Phnom Penh that is supplied by their weavers.

Indonesia

For many visitors, Indonesian textiles have become synonymous with intricate batiks from Bali. However this diverse archipelago has exceptionally fine weaving and natural dyeing traditions that are coveted by textile collectors from around the world.

While much of Indonesian weaving utilizes cotton, it is worth seeking out the special silk textiles that are still being woven today. In Bali, the songket, recognizable by its intricate designs of gold or silver wrapped thread, is worn by brides and grooms across the island and can also be seen in customary tooth filing ceremonies. Visit the weaving cooperative in Sideman village, high in the Unda River Valley, where natural silk dyes are being revitalized.

For travelers heading to Lake Tempe in South Sulawesi, Sengkang and Soppeng are silk weaving centers of the Bugi ethnic group, legendary seafarers and traders whose women weavers still carry out their craft on traditional handlooms located under stilt houses. A little further to the north is Polewali, famous for its silk sarong, the sarung mandar.

Lao PDR

Lao weaving has undergone a stunning renaissance in the past two decades, with the emergence of weaving workshops whose mission is to keep alive traditional silk weaving techniques. These weavers are training a new generation, passing on invaluable knowledge about patterns and natural dyes. Each region and ethnic group has its own silk weaving tradition, focused on practical pieces for daily life, including wrap around skirts (pha sin); shoulder cloths (pha baeng); and baby carriers (pha tai luuk).

Lao weaving motifs are deeply symbolic and can reveal ethnicity, marital status and region. Some motifs are mythical creatures such as the naga, a mythical water serpent who protected the Buddha. Elephants, snakes, birds, diamonds, ancestral spirits are all common motifs that can offer protection or good luck to the wearer.

Lao weavers have renewed natural dyeing techniques in Southeast Asia, using roots, bark, leaves, flowers and seeds. Production of natural dyes is extremely labor intensive.

One fascinating dyestuff is the lacquer resin produced by the Coccus lacca insect. The crushed lacquer is combined with tamarind to make a vibrant red. Many plant dyes require an acid or ash additive to make the dye permanent.

In the UNESCO World Heritage town of Luang Prabang in northern Laos, weaving workshops are abundant. Some, like the fair trade Ock Pop Tok offer weaving classes in weaving and dyeing at their Living Craft Centre. The Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre, also in Luang Prabang has an excellent collection of handwoven textiles on display, along with other nicely curated exhibits.

Some of the finest Lao textiles in the capital of Vientiane can be found at Taykeo textile gallery, founded by Ms Taykeo Sayavongkhamdy, who recreates old motifs to make museum-quality reproductions of antique textiles. On the outskirts of Vientiane, visit Nikone Handicrafts to see exceptionally high quality silk fabric woven by the yard. Nearby Phaeng Mai Gallery is another outstanding silk weaving workshop.

Malaysia

Like its Southeast Asian neighbors, Malaysia has a long and rich tradition of weaving in cotton and silk. Ethnic groups such as the Iban use complicated ikat and floating weft techniques to weave images of animals, reptiles, trees and fruit that have important symbolic meanings in battle and in rituals.

Terengganu and Kelantan are renowned for their gold and silver brocaded silk songket, woven on frame looms with flora and fauna motifs. Just outside of Kuala Terrengganu is the Pura Tanjung Sabtu retreat, a late sultan’s country palace that now offers a homestay experience in a rare collection of 19th century Malay timber houses. The late owner and founder, Tengku Ismail, was a highly respected songket designer who supplied fabric to the Royal Court. The retreat has a weaving demonstration area and fine songket collection.

Sarawak to the east is also known for its high quality songket, unusual for its unique style — thick, highly irregular and technically difficult to weave, having an almost embossed feel. Tanoti House in Kuching has gathered together an accomplished group of artisan weavers under one roof, one hundred percent owned and managed by Sarawakians, with the goal of preserving this special form of songket. Most of their weavers are young women from villages around Kuching, mostly from Asajaya in Kota Samarahan, Gedong and Serian. All trainees undergo hands-on training with the guidance of a mentor.

For many Malay, the finest silk weaving can be found in the small village of Pulau Kuladi in the Pahang royal town of Pekan. To see Sutera Tenun Pahang Diraja, or Royal Pahang woven silk, begin with a visit the Pulau Kuladi Cultural Complex, which is a training center teaching a new generation of weavers.

Myanmar

The art of silk handweaving is alive and well in Myanmar, in part due to years of isolation that have limited the scope of factory production. For textile collectors, the luntaya acheik, a type of longyi (sarong skirt) worn by women of the majority Myanmar people, is one of the finest and most complex examples of Southeast Asian weaving that is still made today. Made on a traditional Thai-Burmese loom, pairs of girls laboriously weave 100-200 small shuttles back and forth through a warp of over 1,500 threads. This creates a distinctive wave pattern, with each design possessing its own fantastical name — Princess’ Curl, Emerald Palace Spring, and Twisted Golden Rope, just to name a few. The acheik is still woven outside of Mandalay in Amarapura, once the royal capital, where silk weaving workshops line the main road into town. A two meter piece takes approximately three months to weave, making it one of the most expensive and sought-after types of Burmese silk.

Like its neighbors throughout the ASEAN region, some of Myanmar’s most striking textiles and weaving traditions are found among its many ethnic groups, which still weave silk with cotton and other fibers. Shan state is well known for its wide range of textiles, some of which are unique in the world. Inle Lake in southern Shan state is home to Inpawkhon village, where silk weaving workshops abound. The Intha people, among others, weave fine silk ikat, known as zinme (‘Chiang Mai’).

Inpawkhon village is also known for its unique ‘lotus silk,’ actually made from the stems of lotus plants. This rare ‘silk’ is extremely labor intensive: it begins with a small bundle of stalks, which are sliced near the top and then gently twisted to separate the fibers from the stalks. The fibers are rolled together on a damp board repeatedly, steadily adding more and more until a continuous length of thread is created. The thread is then wound and made ready for washing, dyeing and weaving. Lotus silk scarves are often dyed the saffron color of monk robes and are used to drape Buddha statues on special occasions. Lotus silk is also woven with traditional silk.

In less accessible western Myanmar, the Chin people weave with silk and cotton on backstrap looms to create exceptional tunics, loincloths, skirts and shawls, often embellished with glass beads, cowrie shells and buttons. A fine collection of Chin and other ethnic textiles can be found at Yo Ya May in the sprawling Bogyoke Aung San Market in Yangon.

Philippines

The Philippines has rich weaving traditions that incorporate a vast array of indigenous materials including pina (pineapple), abaca (banana fiber), maguey (century plant) cotton, and silk, plus embellishments such as beads, stones, seeds, shells and coins. Sericulture, or the production of silk cocoons, has been reintroduced throughout the country thanks to support from the government and international NGOs.

Perhaps the best known contribution that the Philippines has made to the world of textiles is pina fabric, painstakingly woven from pineapple fiber. Embroidered pina has long been the fabric of choice for a man’s formal barang tagalog, but has undergone a revival in the past two decades, showing up in couture collections combined with silk and other fibers. To make pina cloth, pineapple leaves are soaked and scraped of the fibers. The fibers are then dried, waxed, and spun into yarn, which is used to weave the cloth.

Kalibo (the capital of Aklan Province on Panay Island) is the site of the annual Ati-Atihan festival and is also the historic center of pina handweaving. Pina Village is one of the best places to see the labor-intensive pina weaving from start to finish.

On the southern end of Panay Island is Iloilo province, renowned for its hablon fabric. Hablon, derived from the Hiligaynon word “habol,” meaning to weave, is created from brilliantly colored threads made from silk, cotton, pina and other indigenous materials. Hablon was traditionally used to make the patadyong, a Visayas woman’s wrap-around bathing garment. Like pina, it is undergoing a revival thanks to the efforts of the government and local designers. While in Iloilo visit the Indagan Primary Multi-purpose Cooperative in Miagao.

Some of this country’s most distinct textiles are made by ethnic groups who come from less accessible areas of the south, including the Maranao of Mindanao, the T’boli of Lake Sebu, and the Yakan from Basilan Island. Still woven on backstrap looms, these textiles are famous for their stunning dyes and intricate folk motifs incorporating images of nagas, roosters and dragons, often using resist-dyeing, or ikat, techniques. The newly launched Philippine Textile Gallery in the National Museum in Manila has fine examples of these and other textiles from throughout the Philippines.

Singapore

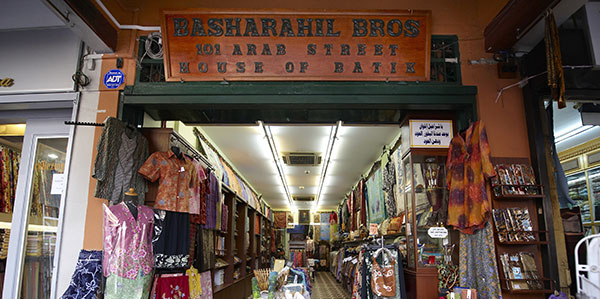

Singapore is a mecca for textile shopping, and silk from throughout Southeast Asia can be found in its enclaves and supermalls. Arab Street has abundant Malaysian and Indonesian handicrafts and fabrics, so keep a look out for shops such as Basharahil Brothers (pictured above) and Hadjee Textiles.

Joo Chiat Complex specializes in Malay textiles and traditional clothing, among other crafts. Here, and at established boutiques such as Rumah Bebe, you can find the traditional Peranakan costume, the gorgeous nonya sarong kebaya. This textile is a multicultural hybrid, combining a traditional Malay form of dress with Chinese and Indian elements including lace and batik. Accessories that accompany the Kebaya are the tali pinggang or waist belt which is usually made of silver, copper or gold plated, along with a beaded purse and kasut manek or beaded slippers. A set of 3 brooches (kerosang) is also used to fasten the edges of the kebaya together. Source: YourSingapore.com.

Thailand

In Thailand, the cultivation of silkworms and weaving can be traced back thousands of years. Thai silk was put on the global map in the 1950s by American Jim Thompson who helped to revive the moribund Thai silk industry before his mysterious disappearance in 1967. For many first-time visitors, Jim Thompson’s house is a must-see on any trip to Bangkok and the fabric and products that carry his name have come to embody Thai silk.

But to see some of Thailand’s finest weaving, including stunning mudmee, or ikat, head to the northeast, or Isan, region, the thriving center of handloomed silk production. Weaving patterns are rich and diverse thanks to the influence of the different ethnic groups that reside there, including Khmer and Lao peoples.

Pak Thong Chai in Nakhon Ratchasima Province is known for its fine plain weave silk, often with a ‘shot’ effect, where the warp and weft threads are different colors. Mudmee is woven throughout the northeast, with each local community having its own distinct styles and designs, incorporating everything from nagas to elephants and peacocks.

While chemical dyes are widely available, some weavers continue to practice traditional dyeing methods passed down through the generations. The lac beetle (red), indigo (blue), and pra hod bark (yellow) are still used to produces natural dyes. For a wonderful overview of mudmee textiles visit the Sala Mai Thai silk weaving museum in Chonnabot, Khon Kaen Province.

Phrae Wa silk made by the Phu Thai ethnic group in Kalasin Province is woven in intricate motifs using the khit and chok techniques, i.e. thrown silk is used for warp and weft while supplementary threads are added to create the motifs. The cloth is used as a shawl or draped over the shoulder on special occasions. The word Phrae means cloth and the word “wa” refers to the length of the cloth, which is about two arms long (approximately 2 meters). Most Phu Thai weavers can be found in Ban Phon village of the Kham Muang district in Kalasin. Phrae Wa silk production has been supported by the royal family since the late 1970s.

Vietnam

Vietnam has become a center for large-scale silk worm and thread production in Southeast Asia, supplying its neighbors where sericulture is limited or disappeared entirely during the war years. At the same time, weaving in Vietnam is rapidly becoming mechanized, with industrial looms in the South dominating textile production. The shops of legendary Hang Gai Street in Hanoi, once filled with handloomed silk shantung and jacquards, are now turning towards factory produced fabrics.

But for the intrepid fabric lover, Vietnam still has many treasures to be found. Villages where silk fabric has been produced for hundreds of years are still producing jacquards made on looms originally introduced by the French in the colonial period. Van Phuc village, just 10 kilometers south of Hanoi, is the historic center of Ha Dong silk production, renowned throughout the country as an important piece of Vietnam’s cultural heritage. The jacquard looms found here control individual warp threads through a system of punched cards. Each jacquard pattern has its own story and place in Vietnamese culture—for example, the pattern ruou tho (wine & poetry) takes its name from a poem by the legendary early 19th century female poet Ho Xuan Huong, who writes of lifting her wine flask, while her backpack ‘sags with poems.’

These textiles are still made by small family weaving enterprises using traditional methods of thread spinning, weaving and dyeing. Dyeing is done by hand in small batches. Because this process is so labor intensive and cost of silk so high, these jacquard fabrics are now largely woven with a rayon warp and silk weft, so that the fabric can be piece dyed, rather than thread dyed. Northern weavers also combine raw silk with cotton and rayon to produce dui, a thicker ribbed Bengaline weave. Traditionally these weavers also made ‘shot’ plain weave silk shantung, where the warp and weft threads are different color, creating a wonderful iridescent effect. This type of silk is increasingly made in factories in Bao Loc in the central highlands of Vietnam.

Vietnam has 54 different ethnic groups, each with their own distinct weaving traditions. Cotton, hemp and now synthetic threads and dyes are the materials of choice, but silk can still be found in some ethnic weaving. Among the Black Thai in northwest Vietnam’s Son La province, for example, young girls were expected to learn how to raise silk worms and make natural dyes using indigo or lac. Hanoi’s Museum of Ethnology has a wide collection of these and other ethnic costumes.

Courney Norris works at Golden Thread Silk a family-owned and operated business in California. Golden Thread Silks got it’s start in the 1990s, when Courtney was doing her master’s research in northern Vietnam. For years she brought home yards of lovely Ha Dong jacquards from the Red River Delta for her mother Deborah’s personal fabric stash. Golden Thread Silks opened in 1998 after the family realised that this unique silk fabric wasn’t available in the United States.